Brigham's Destroying Angel

Being the Life, Confession; and Startling Disclosures

of the Notorious Bill Hickman, the Danite Chief of Utah.

Written by Himself, with Explanatory Notes by

J. H. Beadle, Esq., of Salt Lake City.

Illustrated.

Salt Lake City, Utah:

Shepard Publishing Company, Publishers, 272 State St.,

Opposite Hotel Knutsford, 1904.

William A. Hickman.

[p.v]

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1872. by GEORGE A. CROFUTT, in the office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington.Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1904, by RICHARD B. SHEPARD, in the office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington.

Preface

It was in the Winter of 1868-9, that the editor first saw the subject of this work upon the street in Salt Lake. He was then spoken of generally in Utah as one of the notabilities of an epoch long past. I never heard him mentioned as having any connection with church or civil matters of recent occurrence. For years I had heard of "Bill Hickman, Chief of the Destroying Angels, Head Danite," &c., ad nauseam; but like most persons unacquainted with Mormon history, I regarded such matters as the creations of a fertile fancy. When convinced by a longer residence in Utah that there was and had long been some kind of a secret organization dangerous to Gentile and recusant Mormons. I began to examine the history of the Church more carefully; and while all the Mormon people spoke of Bill Hickman as a desperately bad man, and guilty of untold murders, I was struck by two curious and then unexplainable facts:—

1. The first was, that wile everybody, from Brigham Young down, united in calling Hickman a murderer, and, while evidence could easily be collected of several of his crimes, not a single attempt had been made by priest of people to bring him to justice. For twenty years the Mormons had the courts and juries exclusively in their own hands. During that time many persons had been executed for crime; they could do as they pleased in Judicial matters, and abundant evidence was before them against Hickman; but no grand jury ever moved, there was no indictment, and not even a complaint before an examining magistrate. This indicated something—but what? Until I obtained Hickman's manuscript, I never fully knew. When Hickman was arrested all the Mormon speakers and papers united in denouncing him as "a notorious criminal who had long been able to evade justice." If this was known, as they admit it was, why was not Hickman arrested and punished during that long period in which the Mormons arrested and punished whomsoever

[p.vi] they pleased? Ah, why, indeed—except upon the explanation given in this book.2. The second point is, that long after Hickman was known as a murderer he was successively promoted to a number of offices; he was Sheriff and Representative of one county, Assessor and Collector of Taxes, and Marshal; and during all this time he was on terms of personal intimacy with Brigham Young. He was "in fellowship" in the Church until 1864, and Porter Rockwell, his compeer in crime, is a member of the Mormon Church in "full fellowship" to-day, and now the companion of Brigham Young in his travels! Can these things be explained on any theory, except that the statements in this book are true?

During all the changes of 1869 and '70 I rarely heard of Hickman. At length, in the autumn of 1870, while at Stockton, Utah, I heard the account of his polygamous wife, which is detailed in his confession. A few days after I left there I was horrified to hear of the murder of her Gentile husband—a Spaniard—and the evidence left no doubt in my mind that it was perpetrated by Hickman, assisted probably by one Bates, son of a Mormon bishop. It was reported that he had fled to the Southern part of Utah, and generally believed that he had taken refuge at Kanab, the new Mormon stronghold in the mountains bounding the Great Basin on the south, supposed also to be the hiding place of Burton (murderer of the Morrisites), Porter Rockwell, and other Danites, who, like Brigham Young, have "gone South for their health." But negotiations were in progress for his surrender, as detailed in his statement, and in August, 1871, he was brought to Camp Douglas. He is not confined, as, for obvious reasons, he would not dare return to any of the Mormon settlements, but has the freedom of the camp, with quarters and rations at the guard-room. From this place he sent me an invitation to visit him, and there I first met him face to face. I saw a man of heavy build, round head, and somewhat awkward, shuffling gait; five feet nine inches in height, with bright, but cold blue eyes, of extreme mobility, hair and beard dark auburn—the latter now tinged with gray—and a square, solid chin. His vitality is evidently great, and his muscles well developed. Our conversation need not be recorded, except to say that the man impressed me with his earnestness, and left me with a much better opinion of him than I had before. I then agreed to take charge of his manuscript, and, to use his own language, "Fix it up in shape, so people would understand it."

[p.vii]My first intention was to re-write it entirely, speaking of Hickman in the third person; but one perusal satisfied me that it would be far better as he had written it. I have thought it best, also, to preserve his own phraseology nearly exactly, only inserting a word occasionally where absolutely necessary to prevent mistake. With very few exceptions, the narrative is precisely as written by Hickman and, some faults of grammar and slang terms aside, I think every, critic must admit that our sentimental and religious murderer has a singularly pleasing style. Neither have I thought it best to interrupt his narrative with explanations, but in the more important cases have added the corroborative evidence in an appendix. Late developments in Utah have poured a flood of light on many dark and bloody mysteries, and it is a great mistake to suppose that the recent criminal proceedings against Brigham Young and other leaders were founded upon the testimony of Hickman alone. He only supplied the clew which led to other evidence.

Notwithstanding the publications on the subject, many are still unacquainted with Mormon history. Hence I have given a brief outline thereof in the first chapter, which is submitted to the criticism of the reader.

J. H. BEADLE.

Salt Lake City. Dec. 10, 1870.

[p.9]Chapter I: Introductory History

BY THE EDITOR

Comparison of Mormonism With Other Sects—

Its Inherent Vices—Its Origin and Subsequent Phases—

the "Golden Bible" Speculation—the Community" at Kirtland—

the Fanatical Power in Missouri, and Consequent Expulsion—

Nauvoo—Crime, Politics, and War—Flight Westward—

Settlement in Utah—Hickman Comes Upon the Scene

MORMONISM, unfortunately for man's intellectual pride, is no new thing. From the earliest times history is full of the records of sects and races who imagined they alone had a right to the favor of God. For eighteen hundred years every generation has witnessed new revolts against the pure principle of "Peace on earth and good-will to men"—new sects of fanatics who would wrest the mild precepts of the Gospel, and deduce therefrom license for themselves, and a sanction for vengeance on their enemies. Most often—let the philosopher mark the strange and important fact—these perversions have touched the divinely established relations of the sexes: sometimes to grant one woman many husbands, sometimes to give one man many

[p.10] wives; at other times enforcing celibacy, and at still others setting up a complete sexual communism like the beasts of the field.

Brigham Young.

Inevitably such relations drew after them a mixed mass of social and political results: bloody and despotic governments, absolute power in the male head of the family or tribe, a religion of force untempered by mercy or love, jealousy, hatred, and unspeakable mutilation of young males. The Eunuch is the natural result of a polygamous society, and already several such cases have occurred in Utah.

The very name now blasphemously assumed by the Mormons—"Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day-Saints"—was taken three centuries since by the bloody fanatics of Zwickau and Munster. And their doctrines were so similar to those held to-day in Utah as to excite the astonishment of the inquirer. Mormons in Germany in the time of Luther!

All these perversions of Scriptural marriage exist in some shape, in a few communities in America to-day—Shakers, Free-lovers, Communists, and Mormons. The last has developed the greatest strength, and been guilty of most cruelty and violation of law; and to a complete understanding of the personal narrative which follows, a brief account of the nature and history of the sect is necessary.

Mormonism is sanctified selfishness: a system which teaches practically that very little restraint need be put upon the baser passions; they can be religiously directed and piously cultivated; that the reward of obedience

[p.11] is not within the soul, a pure and hallowed delight, but temporal good and great power in the world to come, where a select few are to inherit all the good and all the others be their servants. To its adherents this gospel, not of humility and self-denial, but of pride and self-aggrandizement, promises substantially this: In a little while they will triumph over all their enemies, and every earthly power shall be put under them; the Saints shall possess the earth, and the unbelievers be trodden beneath their feet; all the farms and property in the country will ere long be theirs, the women and children be their wives and servants, and to all eternity they will glory over the Gentiles. Heaven itself would not be heaven to a good Mormon, unless he could have a few Gentiles to lord it over.Of course such a sect can never be particularly dangerous, or any more than a local disturbance, to a free government; since it is the product of a previous mental slavery, and not of free institutions and free thought. But while it endures it is a grievous local tyranny, and on its members such doctrines must produce a terrible effect. In the very nature of the case, and under the mysterious moral law which governs the universe, such a belief cannot foster humility, long-suffering, charity to opponents, patient kindness, or universal love; its fruits are necessarily arrogance, spiritual pride, wild enthusiasm, and religious intolerance.

I invite the special attention of the reader who cares to inquire, to Mormon literature for the past forty years. In it you will find no deep contrition for sin, no earnest

[p.12] aspirations for humility, no heartfelt recognition of the brotherhood of man, no prayers "that all men everywhere might be free," no lively sympathy for philanthropic societies struggling against a sea of woes and troubles. On the contrary, all Mormon sermons and speeches can be compressed to just this: "We are the Lord's people, His chosen people, His peculiar people, to whom He has spoken by the mouth of His Prophet in these latter days; we know of a surety that our religion is right, and everybody else wrong, and the world hates us because we are right and they are wrong, and we have a perfect right to hate them because they hate us; the world has degenerated; there is no true religion, no real virtue outside of us; men are worse than in the days of Christ, and were worse then than in Abraham's day: the world is ripe and rotten ripe for the harvest of blood and death, and all hell is let loose to rage against the Saints!"Can men who believe this sort of thing ever live in complete amity with their neighbors? That they do believe it I offer in evidence all their so-called theological works. (See P. P. Pratt's Key to Theology; Orson Pratt's Works—particularly The Kingdom of God; the Journal of Discourses; the Voice of Warning; and doctrinal sermons in old volumes of the Millennial Star.)

Nor is their social system other than organized selfishness. The Saint must marry many wives. Why? Because he will thus "build up his kingdom for eternity." But the numbers of the sexes being equal, even in Utah, he must build it at somebody else's expense: if he marries

[p.13] ten wives, nine other men must do without one apiece. He robs his brethren of any kingdom in order to build up his own. Hence the logical necessity of the doctrine, so carefully taught in the works of Pratt and Spencer, that only the righteous are entitled to wives at all! "It follows conclusively," says Pratt, "that from the wicked shall be taken away even the wife that he has, and she shall be given to the righteous man." Who the "righteous" are is, of course, already settled in their minds; the Gentiles, when things get properly fixed, are to have no wives. Can men who entertain such an idea of God's providences have much consideration for God's creatures? Will those who hold such low and imperfect notions of their neighbor's rights have regard for that neighbor's life, or liberty, or property, if he "stands in the way of the kingdom of God"? Can a man be much better than his ideal? Can the devote rise above the standard of his god? Fortunately, most of the common Mormons have not quite entered into the spirit of, or "lived up to," their faith. They were recruited from the industrious, simple classes of northern Europe, and Mormonism has not entirely spoiled them. Nevertheless, I maintain that the ultimate effect of such a faith must be a selfish meanness.Slavery and polygamy—"twin relics"—may well be put beside each other in a brief parallel. As of slavery thus: if a man will steal another man, steal his whole lifetime, his labor, his free-will to go and come—he shows thereby that he has taken one long step, if he is not some distance on the road, towards stealing any

[p.14] other thing he can safely get away with. For what greater good can he steal than a man's liberty and the proceeds of his lifetime? Similarly of polygamy: if a man will crucify the wife of his youth, and put her to open shame, by introducing another woman into the family, and calling her his wife, if he will make misery for two helpless persons and pervert nature's current in the breast of woman, whether for earthly lust or heavenly glory, he shows by that act that he will use another's misery for his own happiness, that he is a long way on the road towards doing any other mean thing which will give him an advantage over Iris fellow-man. Hence a nation of slave-holders cannot long remain a nation of freemen; a race of polygamists is sure to become a race of self-seeking sensualists. Love, forgiveness, kindly charity, must wither in such an air. But this argument, says one, touches the principle of freedom in belief. Granted: the hard fact still remains that some religions are of such a nature that their reduction to practice would render their devotees utterly unfit for amity or even neighborhood with civilized society. The world has known scores of such religions; soon or late they have one and all come into violent contact with government or society, and yielded or been crushed. A religion which makes it the chief hope of its devotee to crush his opponents, not to convert or soften and unite with them, can produce but one class of fruits: hatred, malice, and all uncharitableness, strife and animosity against all who dissent. Hence the Mormon's bitter hatred of "apostates." Other churches pray for the [p.15] backslider; the Mormon curses them with hideous blasphemy. Said Heber Kimball: "I do pray for my enemies; I pray God Almighty to damn them." Said Brigham Young, in his sermon against the "Gladdenites" (Journal of Discourses, Vol. I., p. 82): "Now keep your tongues still, or sudden destruction will come upon you. Rather than apostates shall flourish here, I will unsheathe my bowie-knife, and conquer or die. * * * Such a man should be cut off just below the ears." And again, "I would take that bosom pin I used to wear at Nauvoo, and cut his d—d throat from ear to ear and say, 'Go to hell across lots.'" If such words were spoken in the pulpit and published by the Church, what may we not suspect to have been said and done in secret? Nevertheless, some apologists maintain that the Mormons, despite such a religion, would be first-rate citizens, "if let alone, and granted a State government." Can a bitter fountain send forth sweet water? can a people's whole inner life be bad, and their outer life good? If the Mormons are truly that peaceful, quiet, and industrious people we sometimes hear of, fitted for good citizens, why have they come into violent conflict with the people in all their seven places of settlement? For they have tried every different kind of people, from New York through Ohio, Illinois, and Missouri, to Salt Lake. Are all the people of all those places incurably vicious, mobbers and trespassers on religious right? This is your only possible conclusion, if you start with the hypothesis that the Mormon religion makes its devotees good citizens. The position is false; the facts are [p.16] patent, and sound reason point to but one conclusion: the organization of the Mormon Church is such that it cannot exist under a republican government or in a civilized country without constant collision. This is a strong statement, but as a little monarchy could not exist in one country of an American State, as the Pope's temporality could not continue in the middle of Victor Emanuel's kingdom, so an ecclesiastical organization like that of the Mormon Church cannot peaceably continue in America. It is idle to talk of any compromise, such as Statehood by abandoning polygamy. The Church is a political entity claiming absolute temporal power within its jurisdiction; it must subjugate or be subjugated; it must rule the country it occupies or cease to exist. The conflict in some shape is inevitable. Mormonism is Mohammedanism Yankeeized. What Mahomet sought by his followers' swords, it seeks by subtle means, by perverting the machinery of free government.

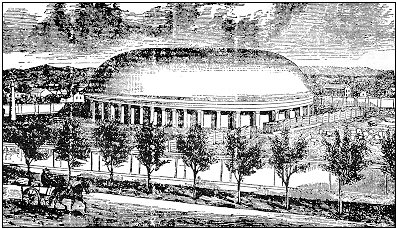

Mormon Tabernacle, in which Brigham advised his followers to

"Send the damn'd Apostates to hell across lots." See Appendix L.

The history of Mormonism is an exhibit of the foregoing principles reduced to practice; a series of attempts by the Church to erect local sovereignties, each defeated by government or people. It has presented no less than five distinct phases.

I. The first was that of the Golden Bible speculation. For the best evidence now shows that Smith and Rigdon scarcely hoped for anything more at first than to create a furore over the "Manuscript Found," and make money by the sale of the work, and that they were as much astonished as anyone else when they found the

[p.18] matter making converts. But they were shrewd and knavish enough to use their advantage, and thus the speculation was the beginning of a new religion. The Pratts came into the organization a few months after; but Mormonism, as it stood for many years, as the basis now stands, was the joint work of Joe Smith, Sidney Rigdon, Orson Pratt, and Parley P. Pratt. It is not known that Brigham Young is the author of any distinct doctrine.But, although converts multiplied, the authors were too near home to work successfully. The young Church emigrated to Ohio, almost in a body, and entered upon another stage.

II. The second phase of Mormonism was as a "Communistic Society," an experiment in religious co-operation, in Kirtland, Ohio. There the "Order of Enoch" was first revealed to Joe Smith, and at that period of Mormon history we first get a glimpse of the "Perfect Oneness" which afterwards played such a part in Illinois. The "revelation" for the first, stripped of all its verbiage, its "verily saith the Lord," and "my servant, Joseph Smith, Junior," simply means this: Each member is to deed his property to the Church or bishop, and hold it as steward, while all outside commerce is to be managed on a joint-stock principle. This has proved most difficult to introduce of all the Mormon schemes, though it has been revived several times since.

The "Perfect Oneness" consisted of an organization of the brethren into quorums of five, over each of which one was a sort of guardian; the property of the others

[p.19] was deeded to this one, so that in case of "vexatious lawsuits," as the Mormons style all suits brought against them, they could prove that it belonged to whichever one was necessary in order to defeat the execution. The Prophet had exercised a great deal of perverted ingenuity on these matters; but it requires no prophet to state the inevitable result. They could, of course, have no other effect than to cause all neighboring people to look upon the community with utter detestation. A mill was erected, a store opened, and a bank established upon the new principle. The brethren were credited at the store, or tithing receipts were accepted, or the goods were let out as pay to workmen on the temple. The result was, when Smith's notes fell due to Eastern dealers, he was unable to meet them; his creditors sued his endorsers, wealthy Mormons who had embarked in the joint-stock scheme; judgment was rendered; the Gentile obtained a judgment; the Mormons "beat them on the execution," and "persecution" followed as a matter of course. The bank enabled them to put off the evil day for a while. It was what was then—in the unsettled condition of banking laws in the Western States—denominated a "wild-cat" bank—that is, it had no charter from the State, and deposited no stocks as security, but its credit rested solely on the wealth of the projectors. Many Western men will remember the multiplicity of such institutions about that time (1830-40), and more than one "Hoosier" will think of the "Brandon Bank Paper," "John Watson Money," "Old Canawl Bank," and the "Kirtland Safety Society Bank," with [p.20] a reflective sense of grief. The elders were sent out to put the notes of the bank in circulation, and worked so industriously at it that in a year they were worth but eight cents on the dollar. Mormons who had invested in these schemes apostatized and sued for their shares; they were thrust out of the community, and appealed to the Gentiles, and, in the words of Smith's Autobiography, "a hot persecution began." Several Mormons were badly treated in the neighborhood; Parley P. Pratt was "egged"; Joe Smith and Sidney Rigdon were tarred and featherod "for forgery, communism, and dishonorable dealing" the mob said—and soon after fled from Kirtland to avoid arrest on civil process. The Kirtland branch of the Church soon followed, and the second stage of Mormonism came to an untimely end.III. The third phase had already been inaugurated, in the form of a wild religious fanaticism in northwestern Missouri. Settlement had begun in Jackson County, Mo., soon after that at Kirtland, and by the spring of 1833 the Mormons there numbered 1,500. Joe Smith had visited the place two years before and delivered a voluminous revelation, which may be found in the Doctrine and Covenants, stating that the whole land was the property "of the Lord and His Saints. * * * The temple shall be upon the center spot lying westward of the town of Independence. * * * * Wherefore it is wisdom that my Saints shall obtain an inheritance in the land. * * * * howbeit, the land shall not be obtained but by purchase or by blood." This was certainly an unfortunate beginning for people who wished

[p.21] to live at peace with their new neighbors. The old settlers laughed at these pretensions, and were threatened with damnation. But real earthly danger soon menaced them: in one year more, at their rate of increase, the Mormons would outnumber the citizens and get complete control of the county, and there was already ill feeling enough for the latter to conjecture too well what kind of justice they would receive.The Mormons now became loud and arrogant: they solemnly announced the judgment of God, immediate and bloody, on all who opposed them; their Sabbaths were spent in "experience meetings," "speaking in unknown tongues," and prophecies of blood upon the unbelievers; they threatened an alliance with neighboring Indian tribes, notified Gentiles that it was useless for them to open farms or settle there, prophesied at one time a pestilence which would depopulate the adjacent country, and at another a war, and proclaimed generally that in a short time "Gentiles and unbelievers would have neither name nor place in all the borders of Zion."

Of course all these matters were greatly magnified, and a thousand rumors spread about the intentions of these "bloody fanatics." It was said they intended to prophesy a pestilence, and then poison all the wells of the State to bring it about; that they were in league with the Indians to rise and massacre the old settlers; that numerous Mormons had secretly got the places of ferry-men, with intention to cause the death by drowning—by apparent accident—of their principal enemies,

[p.22] and that they had arrangements for secret incendiaries to burn near places unfavorable to their religion. About this time, also, we find the first hints of polygamy in Mormon documents, and the first charges of that vice by the Gentiles. The papers published all these matters with inflammatory comments, to which the Mormon paper and speakers responded with threats of defiance.The "old settlers of Jackson County" then issued a call for a meeting "to provide for means of defense," which assemblage issued a public manifesto, which I condense to the principal points: "We cannot," says the address, "trust to the civil law when dealing with a people who do not respect oaths or agreements with those not of their faith. * * * * And when they shall have gained control of the county, let the public judge how we should obtain justice at the hands of men who do not hesitate to depose on oath that they have conversed with the Savior, had visions of angels, and performed all the miracles of healing the sick and raising the dead. * * * * Of their pretense to divine power, their blasphemous utterances, and the contemptible gibberish with which they habitually profane the Sabbath, we have nothing to say; vengeance belongs to God alone. * * * * * But in protection of our common rights, in justice to ourselves and families, and in view of the bright prospects which, if not nipped in the bud, await this young and growing community, we do most solemnly declare—

"That hereafter no Mormons, either individually or

[p.23] collectively, shall be permitted to settle in Jackson County."That those now here on a definite pledge of removal in the future, shall be granted reasonable time in which to dispose of their land and wind up their business. * * * * * * Should any of the Mormons refuse to accede to these conditions, they are referred to those of the brethren who have the gifts of divination and unknown tongues, to learn what fate awaits them."

This sarcastic conclusion was acted upon in serious earnest. The Mormons refused to leave, the citizens rose against them, a sort of civil war ensued, and the Mormons were driven across the Missouri into Clay County with some acts of extreme cruelty.

The Jacksonians have been much blamed for this action, and, indeed, they have but one excuse: either they or the Mormons must leave Jackson; they did not want to go, and so the Mormons had to. With this view the Mormons practically coincide: the perfection of their church system is incompatible with other civilized societies, and cannot exist in the same neighborhood with them. When they become tolerant and amicable, they simply cease to be Mormons. Individual Mormons in Utah at the present time who are social and intimate with Gentiles, always apostatize; Mormonism only becomes peaceful with the world in the degree that it ceases to be Mormonism.

From Clay the Saints spread into Caldwell and other counties, where they prospered greatly for a while. Then political troubles arose. They voted as a unit, and scattered

[p.24] their forces in different counties, so as to wield the greatest possible political power. An anti-Mormon convention unanimously resolved that, "though it cost blood to prevent it, the rule of these counties shall never be given to Joseph Smith." Every species of crime was alleged against them, much of which was shown to be true in the local evidence, collected and published by the order of the State.The same thing was repeated on a larger scale, with more political complications, in the counties north of the Missouri, and in the autumn of 1838 the entire sect was driven from the State.

IV. The fourth stage of Mormonism was as a political independency in Hancock County, Illinois. Six years of local tyranny produced the same effects there, and in 1846 an angry people expelled them violently from Illinois. Most of the native adherents abandoned it, and Mormonism ceased for the most part to be an American Church.

V. The fifth phase we find in Utah: an essentially foreign community, governed by a few swindling Yankees, holding to just so much of original Mormonism as serves their purpose. Here our history ceases to be general, and becomes personal; with the expulsion from Nauvoo, Hickman comes upon the scene as a prominent actor, and I leave him to speak for himself.

[p.25]