Chapter VI: From 1858 to 1865

Murder of Franklin M'Neal—Stealing

Government Stock—Fight With the Thieves—

Huntington Shoots Hickman—Barbarous Surgery—

Attempt to Kill Hickman—Killing of Joe Rhodes—Hickman's

Property "Confiscated"—Departure of the Army—Camp

Floyd—Gov. Cumming Leaves—Gov. Dawson Arrives—His

Flight—Outrage By the "Mormon Boys"—Delight of the

People—Murder of the Prisoners—Jason Luce—Hickman

Goes to Montana—Indian Troubles—Rescues a Train—Arrival of Gen.

Connor and Gov. Harding—Cruel Treatment of the Morrisites—

Hickman Becomes Gen. Connor's Guide—Connor and Hickman

Inaugurate Mining in Utah—Brigham Young Offers Hickman

$1,000 to Kill Gen. Connor—Hickman in Trouble—He Flies

to Nevada—Terrors By the Way—Followed By the Danites, But

Escapes—Returns, and Suffers From Mormon Hostility.

[p.141]

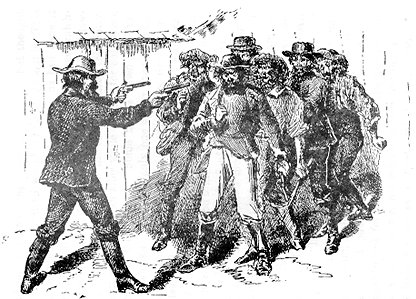

Winter came on, times were lively, and money plenty. One McNeal, who was arrested in the winter of '57, when he came from Bridger to Salt Lake City, for the purpose of making a living, and kept in custody some three or four months by order of Gov. Brigham Young,[p.141] instituted a suit before the United States district court against Brigham to the amount of, I think, ten thousand dollars. McNeal came to the city from Camp Floyd during the winter, and word was sent to the boys, as the killers were called, to give him a using up. The word was sent around after dark, but McNeal could not be found that night, and the next morning he was off to camp again, and did not return until the next summer. I came to town one afternoon, and heard he was upstairs at Sterritt's tavern, drunk. Darkness came on and we got the chamber-pot taken out of his room, so that he would in all probability come down when he awoke with whisky dead in him. Some five or six were on the look-out for him, and among the number was one Joe Rhodes, not a Mormon, but a cut-throat and a thief, who had had some serious difficulty with McNeal, and was sworn to shoot him, and I thought it best to let him do it. Some three or four were sitting alongside the tavern when he came down, it being dark and no lights in front. Rhodes followed him around the house and shot him in the alley. McNeal shot at Rhodes once, but missed him. McNeal lived until the next day, and died, not knowing who shot him; neither did any other person, except those who sat by the side of the tavern. It made considerable stir, but no detection could be made as to who did it. All passed off, and one day when at Brigham Young's office, he asked me who killed McNcal. I told him, and he said that was a good thing; that dead men tell no tales. The law-suit was not prosecuted any further. At this time there was considerable [p.142] stock-stealing from the Government, and, in fact, all over the country, from both Gentiles and Mormons. I did all I could to get those whom I knew of, or was acquainted with, to quit and behave themselves; but it seemed to have no effect. I threatened to get after them if they did not stop. Some then quit it, but others continued, and swore it was none of my business. A few of them took thirty head of mules from a Government freighter and started for southern California; got one hundred and fifty miles on their road, when they were overtaken and brought back by Porter Rockwell and others. As the freighter only wanted his mules, the thieves were turned loose. I was accused of finding this out and sending after them, and shortly afterward seven of them caught me in the edge of town and surrounded me, swearing they would shoot me for having them captured. Three pistols were cocked on me. I tried to argue the case with them, but the more I said the worse they raged, until I thought they would shoot me anyhow. The crowd consisted of about half Gentiles and half Mormons. Believing that shooting was about to commence, and seeing no other show but death or desperation, I jerked a revolver from each side of my belt, cocked them as they came out, and, with one in each hand, told them if fight was what they must have, to turn loose; that I was ready for them, and wanted just such a one as they were able to give. I cursed them for cowards and thieves: when they weakened and became quite reasonable. This all passed off, but I could hear of threats being made by them every few days; when[p.144] one day I came to town and met Mr. Gerrish, of the well-known firm of Gilbert & Gerrish, who said: "I was just going to send for you; we had seventeen head of horses and mules taken out of our corral last night." I told him it had been done by some of the Johnson gang, and I would travel around town and see them; that they were a set of rascals, and I would try bribery. I found this Joe Rhodes of whom I have spoken. He denied knowing anything about them. I told him I would give him fifty dollars if he would tell me where they were. He then asked if I would betray him to the others that were concerned in it. I told him I would not. He then told me if I would give him fifty dollars down, and fifty dollars more when the animals were recovered, he would tell me, and I would be sure to get them. I saw Gerrish, and he told me to go ahead and use my own judgment about them. I paid Rhodes the $50; he then told me they were about fifteen miles away on the river, hid in the brush, and would be there until after dark; then they intended running them south and keeping away from the settlements, and so get them through to California. He described the place so that there could be no trouble to find it. Knowing of the antipathy of the gang against me, I sent two men, who found the stock at the place described, and no one with them, and brought them to the owners. The gang was very angry at this, and swore they would kill the man that had betrayed them. Not many days after this, the traitor to his own party, Rhodes, said I had played him, and he unthoughtedly [p.145] had told me something about the animals, but thought as they were Gentiles I would say nothing about it. This was enough—he never told them that he had done it and got a $100 for doing so. They commenced watching for me, and I for them. One Christmas day following I went to the city, all the time watching this party. I stepped through an alley while waiting for our teams. This was their chance. Some half a dozen of them, well whiskled, met me; only one of my friends seeing them. The only brave man amongst them drew his revolver and attempted to shoot me. I caught his pistol, and would have killed him with my knife, but the scoundrels shouted, "Don't kill him! don't kill him!" and stepped up and took hold of him. I did not want to kill him. I had known him from a boy, and had previously liked him; but these scamps had roped him in, and were shoving him into places where they dare not go. I did not see who all the crowd were, but saw two other revolvers drawn on me. This friend of mine says to them: "Don't shoot; if you do, I will kill you." I let Huntington go, supposing his friends would take care of him, as he was the aggressor, and I had spared his life. I put my knife back in the scabbard, and turned to look for Huntington, when I saw him leveling his revolver on me, not more than ten feet off; I gave my body a swing as he fired, and the ball struck my watch, which was in my pants' pocket, glanced, and struck me in the thigh, went to the bone, and passed around on the side of it. I then drew my pistol; but before I could fire he shot again, and started to run.[p.146] I shot him as he ran, in the hip, and the ball passed into his thigh; but he kept running. I followed him up the street and shot at him four times more, but did not hit him. l was taken to a house, and Dr. * * * * and another, the two best Mormon surgeons in the city, were sent for. They split the flesh on the inside and outside of my thigh to the bone hunting the ball, and finally concluded they could not find it, then went away and reported I would die sure. I sent for other physicians, and the next morning when they came to see me, I told them I had no further use for them, as my thigh swelled and inflamed so that ice had to be kept on it most of the time for three weeks. Then Dr. Hobbs, of the U.S. Army, a cousin of my wife, came to see me, bringing with him a board of physicians from Camp Floyd. They examined my leg, and pronounced the surgery which had been performed on me a dirty piece of butchery, and said: "Were it not out of respect to the profession, we would say they had poisoned it." But when it was finally opened, behold! out of it came a dirty green piece of cotton, saturated with something, I do not know what, which the butchers had left in it weeks before! No wonder they were sure I would die, after leaving that in my leg. While in this situation, these thieves continued their threats to make a break into the house where I laid helpless, and make a finish of me. This Rhodes was the one appointed to do that, as was told on the streets. Rhodes had become obnoxious to all but his party of thieves. He got drunk one day, and swore he would finish me before he slept. I [p.147] had good and trusty men staying with me constantly. Rhodes came, as he had said, and wanted to go into the room where l was, but was told that he could not. He swore he would, drew two revolvers, and swore nobody could hinder him. He started for the door, and Jason Luce ran a bowie-knife through him. He fell on the floor, and never spoke. This was the end of Joe Rhodes. Luce was tried and acquitted.

Thieves attempting to kill Hickman—who, with a revolver in each hand—wants "as good a fight as they are able to give."—Page 142.

I lay in the city three months and was given up to die. I finally was hauled home, but was not able to go on crutches for six months, and never expected to get over it, as I have twice come near dying with it since. I had the fall before bought a few hundred head of oxen which had hauled freight across the plains. My stock was neglected, and I lost a good number of them while I was lying wounded. There was little attention paid to any violation of law there, unless it was a case that was prosecuted by some of the principal men of the city. This case of mine passed unnoticed by the law; and the general saying was: "It was a pity to have a difficulty amongst our own people."

The summer following—'59—the troops were to move from Camp Floyd, and a sale was made of almost every thing except ammunition, which was destroyed. The property sold very low—flour, by the 100-pound sack, 50 cents; bacon, one-fourth of a cent per pound; whisky, 25 cents per gallon; and other things in proportion. I bought ten wagon-loads. The barracks were sold to those who pulled them down and hauled away the lumber; and there has not been a house in the old barracks [p.148] for eight or nine years. The little settlement adjoining across the creek, known as the town of Fairfield, is a nice little village, but is called Camp Floyd, which is my present residence, and has been for the last four years, ever since I left my place ten miles south of Salt Lake City. There was rejoicing when the troops left the Territory. They had come here, spent a great quantity of money, and went away without hurting anybody—a victory, of course.

Gov. Cumming left the next spring, '60. The next fall another was appointed—Gov. Dawson—who, after being here a few months, was said to have used some seductive language to a woman in the city, which raised great indignation against him. He became alarmed, and made preparations to leave, and a company of the young roughs were selected to follow him out and give him a beating. Five went ahead to the mail station and awaited his arrival, and when he came they gave him a tremendous beating; it is said he died from the effects. It was known the next day in town, and most of the people rejoiced over the beating the Governor had got.

This continued for several days, until the word had reached the States, which made a terrible stink on the Mormons, about the manner in which they had treated the Government official. The newspapers teemed with Mormon outrages. This changed things, and then Brigham Young on the stand gave the men who had beaten the Governor an awful raking down, and said that they ought to have their throats cut. Two of them [p.149] were arrested and put in prison, and he forbid any person bailing them out. They went for two more, and they fled, taking with them another man, a friend of theirs. They were followed about seventy-five miles; one of them refused to be taken, and he was shot with a load of buckshot, and only lived a few minutes. The other two were captured and brought to the city, showing no resistance.

They reached the city in the night and were given to the police to put them in prison. While going to the prison they were both shot dead, and the cry was raised that they undertook to get away. That was nonsense. They were both powder-burnt, and one of them was shot in the face. How could that be, and they running? This went down well enough with some; but it was too plain a case with thinking men, and especially those who knew the manner in which those men did such things. A great blow was made as a set-off, how the people killed all who would treat Government officials as those had the Governor—innocence was declared by everybody but the gang who had done it, and three of them were killed, and they said they wished the others to share the same fate. After the other two had been in prison about two months, I went and bailed Jason Luce out. The other got bail in a few days. I then learned all the particulars. Jason told me that he was called on by Bob Golden, who was captain of the police, constable, and deputy sheriff, to go in the country with the others and give the Governor a good beating. Golden said he had his instructions what to have done. Luce [p.150] went to obey orders, expecting to be protected if any trouble should arise from it, he himself having nothing against the Governor, and did not so much as know him. Luce did not like his treatment, and made a business of telling how the affair was. This got Golden down on him, and from that time it seemed that his destruction was sought.9

These things caused a division in feeling among the people; not open, but there was much private talk about such a course of things, which exists until this day. Many of the thinking better class of the people are disgusted with the abominable course taken by the so-called officials, killing off far better boys than their own or many that roamed the country. But their idea was to kill those they did not like, whether guilty of anything or not, as has been done to hide their own crimes, as well as to vent their spite, regardless of right or wrong. This dirty gang of the so-called police commenced about this time, and have done so well they have been kept in office ever since. I will say more about them when I come to the year of their actions.

There was nothing uncommon transpired in '60-'64 more than every once in a while, somebody being killed—some Mormons and some Gentiles—some, it was said, was for stealing and some for seduction, while some of the greatest scoundrels ran untouched. They were good fellows, counsel-obeying curses, and had their friends.

In the summer of '62 I went to Montana after some Flathead Indian horses I had bought the year before[p.151] of the old mountaineer, Bob Dempsy; and that year the Indians were very bad, killing off several trains that were going to California and Oregon on the route north of Salt Lake. This year there was a great cry of big gold diggings on Salmon River, and a good-sized emigration started to that place. I started in company with two boys from here and six Californians, and fell in with a company of forty from Colorado seventy-five miles north on our road. We organized and traveled together. I was unanimously chosen to take charge of the company. We traveled to Deer-lodge Valley in Montana in peace, had a good, jovial set of men and no difficulty. Here we learned that the Salmon River diggings, where the gold was, was four hundred miles further off! Several hundred were alike fooled: some went one way and some another, while about one-third commenced prospecting in that country for gold. We organized in three companies, twenty or thirty in a company, to go in different directions. The company I was in found gold in different places, but not in paying quantities.

I got my horses of Dempsey, and concluded to return home; got on my road, prospecting along the way, when word came that gold had been found in great quantities where East Bannack City now is. I wanted to stop and work awhile, but could not prevail on the five men that were going to Salt Lake to wait; and not knowing any other company going that fall, I concluded to go with them. Provisions were scarce, and none nearer than four hundred miles; some were entirely out; then, and wished themselves away. Two came to me to know [p.152] if I would not take them home with me both poor men. One went by the name of Dutch John, and the other Irish Ned. Dutch John got a saddle, but poor Ned could find none he could buy. I felt sorry; the Indians being so bad that we thought it entirely unsafe to travel with wagons, so I had to leave Ned; but gave him my claim, tools, and fifteen or twenty days' provisions, telling him that was all I could do for him.

But here I must tell the good luck of Ned and my bad luck. The next summer Ned went to the States with $42,000 that he took out of the claim I gave him. I got home the fall before with $2,000 worth of Indian horses. Here was the difference of one man in luck and another out of luck.

Companies coming in told us there was no use of our trying to get through, for the Indians would be sure to kill us. But we had started, and all wanted to go ahead. The next morning I saw the signal Indian fires raised on the mountain, which were kept up all day, raising a smoke opposite us as much as a dozen times. We traveled until dark, got our supper, raised a big fire, and left; traveled fifteen or twenty miles, left the road and got into a deep hollow, where we had good grazing for our animals. The next morning we were off again, and so continued until we got to Snake River, building fires and leaving them, the Indians following us all the while. But when we got to Snake River, where we expected to be out of Indian troubles, no one was there. Tents were blown down, and wagon-covers flapping in the air, and everything looked dismal. My company looked down in [p.153] the mouth. I cheered them up by saying we could whip all the Indians in the mountains. The ferry-boat was across the river. One of my men swam the river, some two hundred yards wide, and brought the boat over. No signs could be seen of any person having been there for many days, and a more gloomy time I had never seen. The Indians had whipped trains where there were eighty men, all armed, and some large trains were all killed off—and we, only seven, all told, with forty-six head of horses and mules, all tired from our hard traveling.

We crossed and struck for the mountain, where we could see all around, and let our animals rest until dark. When we started on again we saw fire-lights, and now the question was, "Indians or whites?" After traveling eighteen miles we got close enough to see that there was plenty of wagons—and began to cheer up, thinking we were safe, and rolled into camp, greatly alarming the people. The Indians had had them corralled four days, two trains together, with the ferrymen. Some of these mountaineers had squaws for wives, and two Indians with them. I was acquainted with the ferry party, but they were as badly scared as the others, knowing the Indians' intentions, and said there were five hundred of them circling their camp, and they were afraid to start. But as soon as it was known I was in camp there was a great shout, "We will get out of here now!" Those that never had seen me would rush up and shake hands, as though there had a deliverer come, sure enough. The brandy kegs that had lain at the bottom of their wagons [p.154] since they left the Missouri River were raised and handed out to us with as hearty a welcome as ever it was to a deliverer of a nation. This was very acceptable to us, for we were almost worn out, and had had no sleep for four nights. My six men looked astonished, to think we had passed through such danger, and asked me if I had realized it. I told them I had, but had kept quiet, as they were all men I had not seen until in Montana.

Next morning a big meeting was held, and I was unanimously chosen captain, with full power to do anything necessary to take them out of the country. We had one hundred and fifty men. I looked at them and thought that about one-third would be good fighting men, and about one-fourth would not fight at all. One man told me that some of the men said they would not fight. I then called the attention of the company, and a vote was taken that I hall full bower to enforce all orders that might be disobeyed. Upon which I informed them that I was a stranger to most of them; that I had been informed that there were some in the company who said they would not fight, even if the Indians made an attack upon us. I asked the question, what should be done with such men, if found backing out in time of trouble. The cry was: "Do as you please with them, and we will back you up." Then I gave orders, if any man refused to fight in time of trouble, to shoot him first; and if there were any who persisted in such a course, to let me know, and if we had trouble they should be placed in front, and if they undertook to run or back[p.156] out, we would first kill them, and have no dead weight to carry.

Meeting of Hickman and U. S. Deputy Marshal Gilson. See Page 190.

A vote of the company was taken to carry out that order. That was the last of men saying they would not fight. All were on hand at a moment's warning.

We rode out, keeping flanking guards and spies on all the mountain points around. I kept the train and stock snug together, and every man with his rifle on his shoulder. Indians were constantly moving around us in different ways. At night, all the stock that could be was tied, the balance was kept in the corral made with our wagons, and a double guard of sixteen men on all the time. We moved on finely until we got to the Bannack Mountain. Here we had to double teams; but only moved a short distance at a time—kept close together, with our spies on all the points around. Just as the last wagon had reached the summit, I saw a smoke rising at the foot of the mountain below us. I saw through my opera-glass Indians coming from all directions, and before we were out of sight there were several hundred gathered at the foot of the mountain where the smoke had been raised. We kept out flanking guards, while passing through the mountain, some five or six miles. We then got into the head of Malad Valley, where we had an open country to travel in to the settlement on Bear River. The Indians gave up the chase, and did not follow us any farther. Two years after this, Gen. Connor having subdued these murderous Indians, I saw one that I had known on Green River sonic eight years before. I asked him if he had [p.157] been one of the bad Indians murdering the whites two years before, and he said: "We did not kill you or your party." He then told me that five hundred of them had corralled two trains and the ferrymen, and that I had got to them when they did not know it. He told me he saw me the morning after I had got into their camp, but did not know who I was; but watched our movement, and soon found that a good captain had got amongst them. They could see no chance to run off stock or take the train, and became satisfied that some great war chief was with them. He said the morning that we crossed the Bannock Mountain, he got into the rocks and covered himself up, only leaving a little hole to see out of, that he might see who that big captain was, and saw it was me. He said he went to the foot of the mountain and raised that smoke we saw for the Indians to gather, and when they all had come, he told them that I was the captain, and they then concluded it was no use to try any longer, for I was a medicine man, and a great war chief. I thought he might be telling the truth, and he, might not; at any rate I would not like to have trusted any of them at that time.

We reached the settlements in good shape, and I went on home. seventy miles farther, and found everything right, and was aiming to live at home and be quiet, attend to farm s rock, and raise my family in peace—not ever intending to again occupy any position in the Church, or as an officer. I thrashed my grain, and seldom went to town.[p.158]

There had been a new governor appointed—Governor Harding, who when I first came home, was spoken very highly of by the people. But soon the story changed, and he was said to be a had man. About this time Gen. Connor—then Colonel—came from California with some three or four hundred troops. Much was said about troops coming into the Territory; but it was thought they would stop at Camp Floyd as before, and probably not be any detriment to the people. Connor had come ahead of his troops, and no person could find out what he was going to do; he never talked beforehand. He went back and met them, and when it was known that he had passed through Camp Floyd, word was sent to him by the head men that he would not be allowed to cross the Jordan River, which he had to do to get to Salt Lake City. But this did not stop him; he kept up his march, crossed the river, and encamped within eight miles of the city. A delegation was sent to him to apologize, or rather deny any such word being sent to him by Mormon authority. The next day he passed through the city and on to the bench, and halted his troops, and established Camp Douglas, which he afterwards built up mostly as it now stands.

The Indians, who had been killing the emigrants for the last two years, had gathered near the north settlements, about one hundred and twenty-five miles north of Salt Lake City. The General sent scouts to seek out their situation, and the Indians sent him word to come on—they were ready, and could whip all his soldiers. The General went with a portion of his men in the winter [p.159] weather, very cold. His men—most of them—waded Bear River, and found the savages in a deep ravine running across Bear River Valley, where it was smooth and clear of knolls or brush, and he had to attack them while in this entrenchment. He had a two hours' fight, and killed over four hundred. But few escaped that could be found, except the women and children, who were not hurt, only through mistake. He had sixteen men killed on the battle-field, and about as many wounded; and some of them died after he got back to camp. This, together with what he did the next spring and summer, broke up this murderous band. He got great praise; and he truly deserved it. That band had killed off several trains of California and Oregon emigration—men, women, and children—sparing none. This was the same band of Shoshonees which had been after me and party.

I had not, up to this time, made the acquaintance of Gov. Harding or Gen. Connor. I did not aspire to honors or of offices, knowing that it would militate against me to be sociable with them. On two or three occasions I refused to go in the room where they were and be introduced to them. One day I was in the city, at Abel Gilbert's store; I saw the door or the back room open, and Mr. Gilbert and the Governor came out. I started out, knowing that my old friend Gilbert would introduce me, and I did not want to get into notice; but, before I got out of the store, I was called back and introduced to the Governor, who said he had been anxious to see me ever since he had come to the Territory.[p.160]

I found him a frank, sociable old gentleman, but anxious to hear me talk, and get my views with regard to the rebellion that was then going on in the States, and a general expression of sentiments. I could not avoid talking, and finally told him I was Southern-raised, and owned negroes, but I thought it a shame to have good and honest men slain to gratify hot-headed aspirants. I told him that the honest men of our nation ought to have taken and hanged about 250 of those hot-headed, rampart Southerners, and about as many of those cursed Northern abolitionists, and then put an estimate on the negroes, and make the negro-lovers pay a part, and also make the owners lose a part; then colonize them and keep a standing army of United States troops, to prevent either white men or negroes passing either in or out of their country, upon the penalty of death. The Governor laughed heartily at what he called my original sentiment.

I thought I was through, and was about to start, when he says: "No, I want you to go back with me." I went, and was introduced to Gen. Connor. The next time I went to town, I went, by invitation, and spent the evening with the Governor; he became very much attached to me. He told me the course he had taken, and the lies that had been told on him, and also the threats that had been made against him; and asked me what I thought he had better do. I told him to attend to business, and act in his official position, fearless or regardless of all consequences. He says to me, "Will you stand by me?" I told him I would, and he might depend [p.161] on me if he had any trouble. Ever after this we were the best of friends; and even after he left here, while Chief Justice of Colorado, he spoke in the highest terms of me in two or three publications he made in the Colorado papers.

The summer previous to this, a sect known as Morrisites arose, and established a church on Weber River, forty miles north of Salt Lake City, under the guidance of one Joseph Morris as their prophet and leader. They sold their possessions owned by them at other places, and gathered to that place to prepare for great blessings that were to be given them from heaven through their prophet. They increased very fast, and were bold in advocating their doctrine. They were peaceable, and ignorant, as a general thing; but had some smart men amongst them, who seemed as steadfast in their belief as those of more ordinary talent. They were hissed and hooted at by those who wanted mischief, and some of them occasionally beaten. Some were arrested under pretense of being guilty of crime, and then would get misused and turned loose.

Finally they made a declaration that they would not be arrested any more for nothing. This was enough. Writs were soon out, and a posse under Gen. Burton was sent to arrest all their principal men. He went some six hundred strong, taking with them a few pieces of artillery, and a fight ensued. Some were killed on both sides. Burton, with his men, shot Morris, and one or two of his principal men, after they had taken their place; and it is said that Burton shot a woman also who [p.162] sauced him. This is the affair for which Burton was indicted in the fall of 1870, and is now on the move to keep out of the officer's hands.10

These people were cruelly treated, and incarcerated in prison to await their trial for resistance to law and for murder. They however got ball, and, I think in February '63 had their trial. The jury being composed of those who were by no means favorably disposed to them, it was a certain thing that they would be sentenced to heavy punishment. The poor creatures were to be pitied; they were as harmless a set of creatures as I ever saw. But the secret of the matter was, Brigham Young wanted them broken up, and it had to be done in some way.

This thing was much talked of, and several of them went to Gov. Harding, seeking redress, and laying their grievances before him. When the court came on to try them, the Governor said he expected executive clemency would be asked in their behalf, and wished me to attend court with him and hear the evidence, so that he might be satisfied in his mind as to their guilt or innocence. I attended court five days, and was myself surprised to hear the flimsy testimony against them. The Governor says to me, with tears rolling down his cheeks like rain. "Have we not heard enough." I told him I thought so, and he says to me, "Why are you so sad this evening? You do not like the manner in which those poor creatures are treated." I told him I felt more like crying over them than persecuting them. He shook me by the[p.163] hand, and said, "I am glad to see those tender feelings you have for suffering humanity; it will all be fixed in time."

The poor fellows, some thirteen of them, were sentenced to the penitentiary from two to fifteen years. Their friends got up a petition for their release, and most of the Gentiles signed it, but very few Mormons attached their names. The Governor asked me if I was going to sign it. I told him I was. He then asked me if I was not afraid of Brigham Young, knowing it was in opposition to his counsel to have any Mormon sign it. I told him no; that "Brigham Young was as afraid of me as I was of him," meaning that we were not afraid of each other. But he has told and published it in the light that Brigham Young was more afraid of me than I was of him. But be this as it may, I would have signed it in the face of all the Brigham Youngs this side of Europe, regardless of all consequences.

Shortly after this, General Connor sent for me—asked me a great many questions about the country, and the mountains, roads, rivers, &c. &c. After getting through, he told me he wanted to hire me as a guide, and might have other business for me to do; that I could stay at home when I was not wanted, but when wanted, would have to furnish my own horse, and be on hand. He wanted me to pilot him to Snake River to see the Indians there, see the country, and go from there to Soda Springs, on Bear River, and locate a military camp for the protection of the emigration. He also wanted to [p.164] catch a small band of Indians that had been killing the emigrants, that he did not get the winter before.

In the spring he, with two companions of cavalry, set out for Snake River, while one company of infantry with supplies, started to Soda Springs, at which place the General told them he would meet them. I went as guide.

The General got to Snake River, found a good many Indians, and had a talk with them, and they promised to be good; and so they will—when they are dead. They gathered by request that night, and had a big dance. The General sent me with a lieutenant and twenty-five men up Snake River fifty miles, and to strike from there south, to Soda Springs, where I was to meet him. I was to look out for a wagon road, as it would shorten the route fifty miles to the Montana mines, where most of the travel was going that summer, he found a good place on Snake River for a ferry, and then started across the mountains seventy miles without a trail, for Soda Springs. We met a party sent out to escort us in, but we would not have missed the Springs a mile. Then the General sent me with a party down Bear River on the north side, with a lieutenant and a party down the other side to look out the practicability of a wagon road down the river. When we returned, the company of infantry had arrived, and the General had located a military post. I continued in the business of guide, and in the fall following piloted the General to Goose-creek Mountain, some 300 miles northwest of Salt Lake City, and from there to Soda Springs eastward, where he had [p.165] the spring before stationed a company of troops. He paid off those troops that were there, and sent me with Lieutenant Finnerty to the Snake River ferry to pay off a posse of troops, which had been kept there during the summer, for the protection ot the ferry and emigration.

We returned, after having paid off the soldiers, to Soda Springs, and started for home on a tremendous cold day. Had a canteen of whisky which we hung up on a bush when we camped. The next morning was as cold as blazes. The lieutenant proposed taking a drink; but no sooner had he filled his mouth than he spat it in the fire, declaring there was sand in it, and said he would give the Commissary hell for putting sand in whicky for him. He poured some in a cup and found it had small particles of ice all through it, which the Lieutenant had mistaken for sand.

General Connor asked me about mines, and said he knew it was not the wish of Brigham Young to have mines open in this country. He asked me also if I had any scruples about it, on account of what Brigham Young had said—I told I had not, and afterwards brought him a good piece of Galena ore from Bingham Cañon, which was the start of mining in Utah. Leads were located, work down, a dn prospecting by different parties continued, many laboring under great disadvantages; but it has continued until now, showing one of the greatest mineral countries in the world. I have located and helped others who have made nice sums of money; but many instances have been neglected, and after putting parties in possession of good leads, with the promise of having a show with them, have had my name scratched off the books, or the lead relocated. Miners, as a general thing, are honest and punctual men; but like all other classes of men, have unprincipled dogs among them.

A goodly number of Gen. Connor's men being Californians and miners, were, when they had nothing else to do, by permission, prospecting the country for precious metals. They made many good discoveries, and organized districts. They located leads in Stockton, the Cottonwoods, Bingham Cañon, East Cañon, and other places; and it can truly be said of the General that he was not only a good general, subduing the hostile Indians, and maintaining his dignity as a commander of the Utah district amidst many brawling outrages of the people of Utah, but was the main developer of the Utah mines against all opposition of the principal men. He in this, like all other business, took his own course quietly along, regarding them as a big cog would the barking of fists, or a locomotive the buzzing of flies.

And here I will state that just before this I had my last break with Brigham Young. In the spring or early summer of 1863 I went to town, and Brigham Young sent for me. When I got to his place he said: "That Gen Connor is nothing but an Irish ditcher, and don't belong in this country, and you are the man to get him out of it." After some more talk he said: "If I would kidnap Connor and set him over into California, he would attend to the help and give me one thousand collars, and all expenses paid." I laughed at this, and [p.167] made no reply. Nobody knew then how I stood, and I did not know how they looked on me. Six months after that Brigham Young repeated his previous conversation with me, and said Connor was a bad man, calculated to do a freat deal of injury to this people, and ought to be used up. "Now," said he, "you are the man to do it; you travel with him as a pilot and guide, and you could easily do it, and it could be laid to the Indians. You can have a great deal more money that if you had kidnapped him and taken him to California." Then I spoke up to Brigham Young for the first time in my life, and said I would not do it; that General Connor was a good man, and the best officer ever in Utah, and I knew him to be an honorable man; "and what is more," said I, "it shan't de done; I will see to that myself. I will look out for that." I was rash and stirred up, and spoke sharp, which had not been the way with us in talking to Brigham Young.

The second winter I was in the General's company he told me he had lost twelve head of mules from the Government reserve in Rush Valley, and wanted me to hunt them up, as I had done before when animals were lost or stolen. I searched several days, but no trace of them. I returned and made my report to him. He sent me again, saying to me, if any man could find them I could, and wished me spare no pains in hunting. He said I might resort to any stratagem I could, and he would back me up. I was satisfied in my mind who had stolen them, and employed men to assist who I knew they would not mistrust. I soon found where the mules were, and[p.168] in learning this I soon found out that the same company had been committing burglaries for several months past, and then had in their possession several thousand dollars' worth of stolen goods. I reported to the General. He sent and got the mules. I made known to the Captain of the Police in the city what I had found out about the burglaries, and who had committed them, and where the stolen goods were. He raised a posse of the sheriff, policemen, and others, and I accompanied them. We found the goods, arrested the men, and took all to the city. I went home supposing I had done a good deed and would get the reward that was offered for them—three hundred dollars by one man, and two hundred by another. But what did I find when I went to town a few days after? I found the reward-money drawn by their confederates, the police, and a writ in their hands for my arrest, made out on complaint of these burglars with whom the goods were found. I was arrested late in the afternoon, and took a good man with me to go my bail, who swore he was worth thirty thousand, liable to execution. The Probate Judge said it was not sufficient, and I would have to get another worth as much inside of an hour or go to the cells.

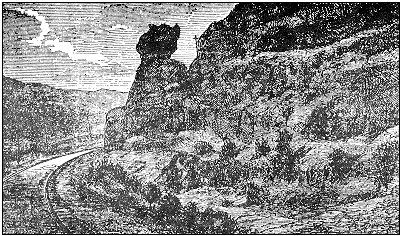

Pulpit Rock, mouth of Echo Cañon, where Brigham Young preached his first sermon in Utah, and where Yates was murdered by Hickman.

Now, this dirty old villain knew I was innocent, but he was a confederate with this well-known clan, the so-called city officials, sheriff, and policemen. A blacker set of scamps I never knew. I got another man who swore he was worth one hundred thousand dollars, liable to execution. I then was reluctantly let go after giving one hundred and thirty thousand dollars bail. This may seem [p.170] strange, but when you see their motives it will be plain. I was in the Government employ, stood fair with both city and military officials, and all hands had set to break me up, stigmatize, and even kill me for taking the course I did in rendering Government. official help.

I had a long trial; but finally got out. They became alarmed, and after I had been in court five days I told the prosecuting attorney that I would give him just one hour to enter a nulle prosequi in my case, and write the facts about it and give it to me to be published in the next day's paper, or I would use up his thieving one-horse court with all its theiving officers. The consequences were my request was fully granted, in ample time. These villians from that time to this have sought my live. But I must tell you what they did with their chummies, the burglars; they let them go on promise of some time paying two hundred dollars apiece. It was only a few days after this they were caught in a cellar in the city. The. officers having no one to lay their crime upon, they were sent to the penitentiary for three years each, not having done anything only being caught in a cellar where goods were stored away. But when caught with several thousand dollars' worth of stolen goods in their possession, they were released without punishment. This was no uncommon thing for parties who were guilty of great crimes to go unpunished, while those of minor offences were given heavy sentences. This court was a gang that cut; and dried many of their cases in the "counsel" before they would come into court;, and then carry out their spite upon whom they pleased.

About this time they caught me on a bail bond for two hundred dollars and costs. I had gone bail for the appearance of a man that I knew was not guilty of the charge against him; but when going to Montana, in '62, I delivered him up to the court. They let him loose for some time without any recognizance, and he finally went to California. This old bond, which I had neglected taking up when I delivered up the prisoner, was sued on, after only four years with not a word said about it. But this was the day of vengeance on me, and this corrupt court had all power, and made me pay it with costs, saying, " If he does get money out of the Government, we will try and ease him of all we can."

I had a good stock of cattle—near two hundred head—when I went into the employ of Gen. Connor. I did not dispose of twenty head, and yet, when the war ended and Connor went out of office, I did not have twenty. My friends, of those who should have been my friends, had the good of them. I have been told by good honest people, that they heard their bishop sat it was no harm to kill and eat my cattle.

When the cattle were used up, then they commenced on my horses, and in two years I lost about three thousand dollars' worth; and to show that it was all aimed for me, the last raid that was made I had five horses in the portion of the band that was stolen, that I had bought and had not put my brand on them, and they were all turned out of the band, and I found them some thirty miles from home. The balance were run into Nevada; but I did not hear this until it was too late to find them.[p.172]

Well, what next ? I was one of those men who had a plurality of wives, and had children by them all. I had as quiet a family as any one I ever saw of that kind, and what I had done in that matter I had done in all good faith. I had not violated the Congressional law of '62 prohibiting polygamy. Neither did I ever expect to, '58 being the last year I had taken a wife. I felt under obligations to take care of my wives and children; but, to use their own language about me, they seemed determined to use me up. The Bishop and others would say to my wives that I was a bad man, and commenced persuading them to leave me; and they would see that they took their children with them, and I should give them all they would ask. They soon got things going, but never had the pleasure of making me give them a dollar; for I told them to help themselves and take all they wanted. I many times would ask them what I had done, and what was wanted of me? Their reply was, "Oh! you have been with the Gentiles and their dirty Government officers and have betrayed us; it is you that has put Gen. Connor in possession of all the news that has gone to Washington about the Mormons." I would tell them that I had not, and even went so far as to have the General say he had never heard me say anything about the Mormons that would be criminal; but all this seemed to do no good whatever.

About this time, one of Joseph Smith's sons, from Illinois, came to Utah and preached several times, always raking Brigham Young for his misconduct and digression from the principles of Mormonism. The general [p.173] feeling was very bitter against him. I went to see him, as I told him, out of respect to his father, and we had a general social chat. This was enough: what I had not done before, I had done now, and I was in for what was called "Josephism," and that was enough to damn anybody. I saw I could do nothing in this country, and concluded to leave. I sold my place, farming utensils, &c., repaired my wagons, and got teams ready to start. I was abused by every low dog that came along, for being an apostate. I tried to argue with some about the necessity of my going away under the circumstances, but it was of no use. A great many said they did not blame me, and would go, too, if they were treated as I had been. About the time I was really to start, I got word from my friends that there was no use of my trying to get out of the Territory with my family and stock, for they were watching the roads, by order of Brigham Young, and I would be certain to be killed.

Then I did not know what to do. I concluded I would go and see Brigham Young. I told him how I was treated, as I had before done. He made very strange of it. He wanted to know by whom. I told him the names of some of them; upon which he sent R. T. Burton, the sheriff, to make inquiry. Of course he knew nothing, he being Brigham's dirty jobber, as he had been for eight or ten years. Brigham Young promised to have things looked to; but when I told him men had been prowling around my house several nights with guns and pistols in hand, he gave me strict orders not to shoot any of them. I begged him to give me the privilege of defending[p.174 ] myself; but he said, "You must not hurt any one," the reason being, they were some of his men, and he knew it. He professed great ignorance; but I knew no such raids dared be made without his orders. I talked to him some time, watching him very closely, and finally came to the conclusion that he would call off his dogs, or rather his murderers, and let me alone.

I went home and all was quiet, even those whom I had seen watching my house came round and were very friendly. I still wanted to leave, but seeing the situation of my family—that I would have to leave my children in the hands of those I abhorred, I concluded to round up and live in this country, and do business for the Government, and be the friend of the Government officers, without losing all of our property, and then have a gang of murderers and robbers always seeking our destruction.

About this time the Sweet-water mines were discovered, and I, in company with others, went to wee them, it being in the same portion of the country I had prospected in 1855. I heard when I left home that a company of men had followed me, learning I was going to leave the country. I staid at the mines about a week, the last day I was there in company with one man, I went some ten miles off prospecting, saw Indian signs, and two Indians hiding behind the rocks. We did not go near them, believing they intended hostilities, but kept a good lookout, leaving that place and taking a circuitous route for[p.175] camp. After we had gone two or three miles we saw about a dozen Indians trying to get around ahead of us, but both being on the best animals, we soon got out of all danger. I told at camp what I had seen, and that there would be trouble, but could get few to believe it. I then told them I had only a day or two longer to stay, and if they did not go to work and organize, I would start home the next day. There was then about one hundred and fifty men camped in squads up and down the creek, but no organization was gone into. The next morning I, in company with ten others, left for Salt Lake. The next morning the Indians made a raid on their camp, killed three men, and ran off near a hundred head of horses and mules, over half they had. We were overtaken by some of the fleeing party before we got to Green River, a distance of sixty-nine miles.

I returned home, and thought I would get some cheap place, and do the best I could until things would have a change. I bought a small ranching place at the mouth of Bingham Cañon, moved my family and stock there, built a good corral, and commenced to improve. I bought seventy-five head of Spanish horses, and intended to do ranching and stock-raising business. But to my sorrow, I soon saw that I was again watched; men were prowling around day and night, some of Brigham's jobbers. I understood it, knowing his motions so well. I commenced laying out in the brush. I saw two men go into the tent where I was in the habit of sleeping. They had a pistol in each of their hands. This was what I expected, and feared being shot in bed. Two nights after[p.176] I saw two men go in the tent again, and two stood outside with guns in their hands. I concluded that there was no use for me to try to live here any longer. The day following I saw one of the party, a man to whom I had done several favors, and I rounded him up and demanded of him what was the cause of this. He agreed to tell me all provided I would not expose him. He said it was not believed I intended to slay in the Territory, and that I was confederate with the United States Judge and Marshal, and was assisting them to knowledge against the Mormons in the murder of Doc. Robinson and others; but if I would go and buy, a good farm, and sell off some of those wagons and horses, and make a full showing that I intended staying here, I would be let alone. I would have done this for the sake of seeing my children raised; but seeing there was no truth or honor in Brigham Young, and his promise amounted to nothing, there was but one show left for me, and that was to get away quick, and not be overtaken.

The night before I left, one of my boys, being out, was chased by this same gang, thinking, I suppose, it was me. Now those watching me were men with whom I had never had any difficulty; but were of that kind that would kill father or son at the bidding of Brigham Young. This may seem strange, but there are plenty such in this country, that believe they would be doing God's service to obey, if Brigham told them to kill their own son, or the son to kill the father. For two reasons: One for obeying the great command of Brigham, and having nerve enough to do the deed; another, that the [p.177] man had done something that his blood should be shed to atone for his sins, and it thereby would be the means of salvation to the murdered man, and honor, and a promise of greater exaltation in the world to come to the slayer. But let me here say that this is all Brigham Young's doctrine; I never heard of any such thing until I had been here several years. Those doctrines of shedding a man's blood to save him,11 Adam being God, and several other abominable things of like character, have originated solely from Brigham; obedience to the requirements of the Gospel, as set forth, taught, and understood heretofore by the Mormons, have almost entirely been set aside, and the general teaching is, and has been, to obey Brigham Young's counsel and that of his bishop. Many is the time that at public meetings the people have been taught that the Bible, Testament, and other books of the fenner Mershon faith were of no use; that those things were good enough in the time of them; but now we had the living oracles with us, and that all divine record was of no more use to us than an old newspaper. Brother Brigham was our Saviour, and would lead us to Heaven; he held the power of salvation for all in his own hands, and had his officers, who administered, such as bishops, etc. The great and all-important teaching to the people is: Obey your bishops, and pay your tithings, and you are sure of being saved. This may seem strange to those who have never heard of such things before; but I assure you there are hundreds in this Territory who are sanguine in this belief[p.178] even now—and as for Mormonism, there is no such thing in this country; it is all Brighamism, and should be called so.

The morning before I left two of those dogs were at my place, very inquisitive about what I was going to do. I told them I was going to conference, and expected to attend every day. This seemed to ease them, and they left. I had also learned that the roads were watched in case I made an attempt to get away. I mounted one of my best horses, and, with a few days' provisions in my saddle-pockets, struck across the mountain west, and did not strike a road for 150 miles. Meanwhile, these special friends called every day to know where I was. The answer was, that I was out hunting my stock; but they smelt the rat, and three men were after me, but were too late. I was not seen on the road until I got to Deep Creek, nearly two hundred miles west, at which place I stayed one night, telling them my business was two hundred miles further, to Austin, to search for some animals that were stolen the spring before. This place was six miles off the line between Utah and Nevada. I knew I was ahead of all the time they could make after me, even if they intended following me; so I took things easy from there to Austin. When I got there I found plenty of acquaintances and friends—the Marshal of the city, Hank Ney, and Benjamin Sanburn, the Sheriff, together with the mail agent, Len. Wines, whom I had known from a boy, Charley Stebbins, and others. I was kindly received and well treated; had an introduction to most of the principal men of the city. I found [p.179] in the city one mule I had previously lost; had him replevied, and, according to the best information that could be gotten, he, in company with some five or six head of other animals, were brought there by a Salt Laker. After I had been there about two weeks, a man came in town and told me I had been followed to Deep Creek by three policemen; but I had been gone five days when they got there, and they wished him, if he saw me anywhere, to telegraph to them to Salt Lake City. He asked then what charges they had against me, and they told him (he being a Gentile) that I had killed a Gentile close to the city some months before, and that was why they were after me. He told me he knew they were lying, for he had been there himself, and nothing of the kind had occurred. He said they swore if they caught me they would kill me without saying a word to me. They were beaten, and the dirty dog, who is one of Brigham Young's blood-shedders, Sam Bateman, who was in charge of the party who were watching me, made great lamentation, saying he had lost three weeks watching me, and I had got away at last, and would bring great trouble on Brother Brigham.

I got letters from home, in which I was advised to not come back until things took a change. I then concluded to go to California and spend a month or two. I went to San Francisco, found my old and true friend, Gen. Connor, and many other acquaintances; had an introduction to the Governor, and a great many others, and had a good sociable time. I told the General what situation I was in, and got a statement from him, with [p.180] the signature to it, that I had never at any time made any disclosures to him on Brigham Young, which I sent home.12 I then went over the mountain, back into Carson Valley, where my old partner lived that I had mined with in California in '51-'52. I got letters from home saying things had quieted down, and Brigham Young told my son to write for me to come home. But I had made up my mind never to return again, and intended to take shipping from San Francisco to New York, and from there take the cars to Western Missouri, and send for my family.

But just at the time I got ready to start I was taken with typhoid fever; it fell into my lame thigh, and it swelled up as big as a common flour sack. I suffered all that a man could suffer and live. I was reduced to skin and bones, lying on my back for four months, run off from my family, amongst strangers and just alive, for no cause whatever, only the fears of my making statements of Brigham Young's course in Utah. I cannot express my sufferings of both body and mind. Night after night I would lie, scarcely able to turn over, no one to speak to; and was given up to die by every one who saw me for weeks. Language would fail me to begin to tell my feelings. I was innocent of crime, only the obeying of Brigham Young's orders, and would sometimes say, O my God, may the day come when his unjust reign shall have an end!

WASH-A-KIE, Peace Chief of the Shoshone Indians See Page 105.

Finally some of my old acquaintances, Mormon apostates, whom I had befriended while in Utah, came to my[p.182] assistance, and took care of me until I got able to help myself. My old mining partner being a bachelor, and about that time taken sick himself, I had to stay with those whom I had never seen. Notwithstanding all this, I continued to take the part of Brigham Young in all conversations, with the exception of talks to a few confidential friends. I was down-hearted and disconsolate, and did not much care what became of me. I concluded to return home and take chances again. I went to Virginia City to take the stage, for home, and there found Gov. Durkee—then Governor of Utah—who had been to California, and was on his way home. We procured the same seat in the coach, and had a general chat on Utah affairs. He seemed to know all about my situation, and advised me to take care of myself. He said if it was in his power, such a course of things as was going on in Utah should be stopped; but as he was unable to do anything, he would try and serve out his time quietly, and then leave the Territory.

On reaching home, after resting a few days, which I very much needed, being weak and going on crutches, I, with my wife, went to see Brigham Young. He seemed to express great sorrow for me, made inquiry of the cause of my leaving, and, on my telling him how things had stood, he said I should have come to him. I told him I thought I had said enough to him, and it all seemed to amount nothing. We went to our home where my family had been moved: to some forty-five miles south of Salt Lake City, where they had purchased some houses and lots, and were in a tolerably comfortable situation.[p.183]

I then commenced looking after my scattered family. I had left three wives at home, besides my first, all living in as much peace as any family of the kind. I found one married to a black Spaniard. This woman had four children, the oldest being a daughter of eleven years. Another wife was just ready to marry, which she did in a few days after I got home. This was all right, as I had, after leaving the fall before, been disfellowshiped from the church. I was then left with two wives—the first and the last—the last having two boys, one six years old and the other four. I was disfellowshiped without any charge being preferred against me, and on inquiry learned it was for going away without permission.

I went to mining, and attended to what stock I had left. I did not find half I had left at home when I started away. I soon heard rumors of trouble on me. I went to see Brigham Young, and wanted to know what charges were against me. I found that the same old thing was up again. I was accused of telling Gen. Connor all I knew, and that the evidence had gone to Washington, and had come out in pamphlet form, and I was the cause of all of it. I reminded him of the letter I had sent him with the General's signature to it. He denied ever seeing such a certificate, and I told him to wait until I could write to San Francisco, and I would have another. I wrote a letter to the General, read it to him, and gave it to one of his clerks to put into the postoffice. I soon got an answer, with the same statements in it that were in the one I had got before. I took it to him; he read it, and says: "Well, may be[p.184] so." I asked him if there were any other charges against me. He said yes, I had been intimate with the Smith boys, Joseph's sons, of whom I have spoken. I told him I only went to see them out of respect to their father, and never had a private chat with them. This he was not disposed to believe. l went and brought John Smith, cousin to them, who is one of Brigham Young's officials, and had him state that nothing outside of a common conversation took place between us. I asked what more was against me, and he said he did not know. I asked him why I was disfellowshiped. He seemed beat, and was mad, and said, "If it was not right to have done it, it would not have been done," and got up and left. I have not spoken to him but twice since, both times on business. He wanted to know the last time I saw him if I was going to join the Church again. I told him I had for three years tried to find out what was against me, and could not; consequently, I expected to remain as I was. He said he would give me a recommendation to the bishop, and wanted me to be baptized again. I told him that would be an admission of guilt which he and all others had failed to show. "Well, well," says he, "I will fix all that." This was the last of it. I have not seen or spoken to him since. I had no desire to belong to his Church, but would have accepted a reunion for the purpose of having more peace and a better show to do business and raise my children.

Bryant Stringham, the man who took care of what was called church stock, hired me to gather up what stock they had in Cedar Valley, the valley in which I [p.185] lived. Stringham was a good, honest man, whom I had been acquainted with for more than twenty years. I went at it, got up his wild horses, and traded them off for cattle, and some I sold for money, doing as he had ordered, not charging half as much as others did, thinking when Brigham Young heard it he would be pleased. But to the reverse; he gave Stringham a blowing up, and made him go and advertise that I was not a church agent to gather up stock. Stringham settled with me, like a gentleman; but I could do no business that Brigham Young could prevent. This is only one of several things he hindered me in.

(ZCMI Plaque)

[p.186]